Identifying and Eliminating EAB

It can happen suddenly; that tree that provides a lot of quality shade for the back patio looks sick. The canopy isn’t as full as it once was, and it’s losing leaves at the top. What’s going on with it? Is it Emerald Ash Borer? Can it be saved?

It can happen suddenly; that tree that provides a lot of quality shade for the back patio looks sick. The canopy isn’t as full as it once was, and it’s losing leaves at the top. What’s going on with it? Is it Emerald Ash Borer? Can it be saved?

Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) is increasingly the cause of decline and death in ash trees. Since spring of 2015, when EAB first appeared in Lancaster County, these pests have been spreading throughout our area. Below you’ll find an easy reference guide designed for the average homeowner. Let’s start at the beginning:

How To Identify An Ash Tree

Ash trees are the only trees susceptible to damage from the Emerald Ash Borer. There are several species of Ash tree. These are identified by opposite branching, meaning leaves come off the branch symmetrically, with a single leaf at the very end of each branch, meaning there will always be an odd number of leaves on each branch. On Ash trees, there will be between 5-11 leaflets per branch. Ash leaves are usually long, almost oval shaped. Depending on the species, edges of the leaves can vary from smooth to fine-toothed, serrated edges. There are some exceptions, but for the most part in Pennsylvania landscapes, the bark will have a thick, diamond-patterned bark. If you are unsure, contact a Certified Arborist to help you with the identification.

Ash trees are the only trees susceptible to damage from the Emerald Ash Borer. There are several species of Ash tree. These are identified by opposite branching, meaning leaves come off the branch symmetrically, with a single leaf at the very end of each branch, meaning there will always be an odd number of leaves on each branch. On Ash trees, there will be between 5-11 leaflets per branch. Ash leaves are usually long, almost oval shaped. Depending on the species, edges of the leaves can vary from smooth to fine-toothed, serrated edges. There are some exceptions, but for the most part in Pennsylvania landscapes, the bark will have a thick, diamond-patterned bark. If you are unsure, contact a Certified Arborist to help you with the identification.

Where Did EAB Come From?

The Emerald Ash Borer itself is a beetle that is native to Northern Asia and likely traveled to the US in shipping materials, like pallets. The only native predator it has is a woodpecker, which is also damaging to your Ash trees, and even then woodpeckers only feed on the larval stage of the insect’s development. There are no native predators for the adult beetle.

The Emerald Ash Borer itself is a beetle that is native to Northern Asia and likely traveled to the US in shipping materials, like pallets. The only native predator it has is a woodpecker, which is also damaging to your Ash trees, and even then woodpeckers only feed on the larval stage of the insect’s development. There are no native predators for the adult beetle.

How Does EAB Damage A Tree?

EAB causes damage to trees in its’ larval stage. The larvae feed in what is called the cambium layer of the tree, just below the bark and typically create an S shape gallery pattern. The tree’s bark protects this layer from damage since it is here in the cambium that moisture and nutrients flow up from the soil to the very heights of the tree; think of this layer as almost like the veins in the human body. EAB larvae feed in this layer by digging tunnels in it, which prevents this flow of water and nutrients. It is the slowing of this flow of nutrients and moisture that causes a decline in the tree (when it starts to drop leaves). When the EAB larvae has made a tunnel around the entire circumference of the tree, completely preventing nutrition and water from reaching the leaves and branches, the tree dies.

EAB causes damage to trees in its’ larval stage. The larvae feed in what is called the cambium layer of the tree, just below the bark and typically create an S shape gallery pattern. The tree’s bark protects this layer from damage since it is here in the cambium that moisture and nutrients flow up from the soil to the very heights of the tree; think of this layer as almost like the veins in the human body. EAB larvae feed in this layer by digging tunnels in it, which prevents this flow of water and nutrients. It is the slowing of this flow of nutrients and moisture that causes a decline in the tree (when it starts to drop leaves). When the EAB larvae has made a tunnel around the entire circumference of the tree, completely preventing nutrition and water from reaching the leaves and branches, the tree dies.

How to Spot EAB Damage

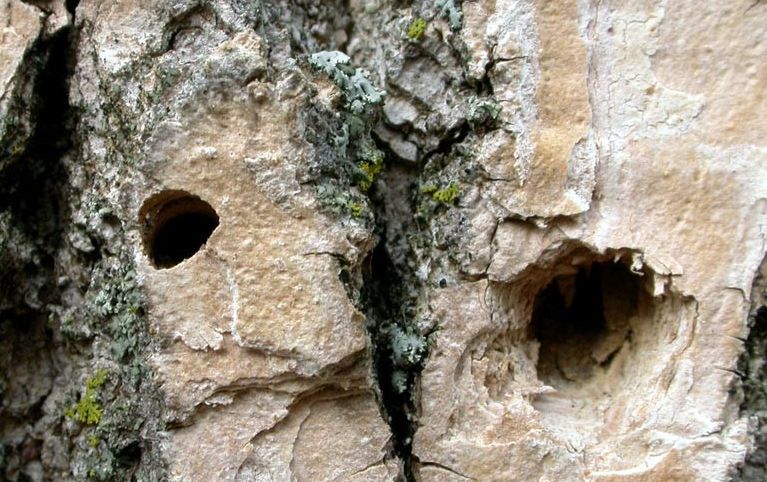

If you have an ash tree that is starting to show signs of decline, you should look for small “D” shaped holes in the bark of the tree. Larger holes where the bark appears to be damaged significantly could indicate that the tree has EAB, but that woodpeckers have been feeding on the larvae. The adult EAB is small (it easily fits on a penny) and is a bright, jewel green color. Canopy decline in your Ash tree will start as thinning at the top of the tree (leaf cover isn’t as dense at the top as it is near the bottom). Once the canopy has declined about 30%-35% from its pre-infestation stages, your tree is likely beyond saving.

Can I Do Anything To Save My Tree?

The short answer is “maybe.” It largely depends on the state of decline the tree is in when you call someone for help. As a rule, if you know you’ve got an Ash on your property, the sooner you do something, the more likely you’ll be able to save your tree.

You generally have three options: treatment, removal, or do nothing. Doing nothing is the least desirable option since a dead or dying tree nearby poses a threat to people and property.

That leaves you with treatment or removal. Removal, while an option, can sometimes have it’s drawbacks as well; access for your tree service is a consideration, not to mention the cost of removing a tree and grinding the stump. In each year, the most cost-effective option is almost always to have a healthy tree treated. You should still seek the opinion of a Certified Arborist.

Treatment is done in one of two ways, depending on the size of the tree in question. For smaller trees, a soil-applied insecticide is used. The soil is drenched with the insecticide, which is absorbed by the tree through its root system. The product stays inside the tree once absorbed, and insects that try to feed on it are controlled. The product eventually breaks down harmlessly, but this necessitates repeat applications annually.

For larger trees, often they are injected with the appropriate dose of insecticide. This is only done on larger trees because smaller trees often won’t survive the drilling process. Larger trees, however, readily grow new bark over properly drilled holes, and uptake the material like they are drinking water. (Incidentally, this is really cool to watch!) Often, this process only needs to be done every other year instead of annually, like the soil-applied insecticide for smaller trees.

If you have further questions about this process, please don’t hesitate to contact us! We’d be happy to speak with you about the needs on your property!